MAJOR HENRY QUALTROUGH MBE 1924-2012

Articles from the Isle of ManPart 1 of 2

From theIsle of Man Todayby Mel Wright and his obituary fromthe Independent by Anne Keleny

FATHER AND SON: The late Henry Qualtrough pictured with his son John

after receiving the George Medal for bravery

The life of a Castletown man whose heroism earned him one of Britain’s highest awards for bravery - the George Medal - was celebrated in a service at Malew Parish Church on March 13.

Henry Qualtrough - who died, aged 87, on March 8 - was educated at King William’s College, Castletown. At 18, he joined the army. On his 20th birthday – June 6, 1944 (D-Day) - he took part in the first wave of Normandy landings at Gold beach and was tasked with clearing the beaches under heavy enemy fire. Out of 40 in his troop, just two men survived (Henry was wounded).

In 1948 he was posted to Elgin, north-east Scotland, where he moved with his wife Audrey (they married the same year). They had two daughters, Heather and Roxana, and their son John was born in 1957. In 1951 the family moved to Singapore/Malaya, where he was involved in the Malayan Emergency - the guerilla war between Commonwealth armed forces and the Malayan National Liberation Army. He was posted to Hong Kong in 1958 and became involved in bomb disposal work, for which he was gazetted for an MBE in 1960.

After a further stint in the UK, he was posted to Gilbert and Ellice Islands for bomb disposal work, from 1965 to 1966. The job was to assess and later clear the island of bombs and shells left by the US and Japan during the Second World War. By then ranking as a major, he and his“trusty sidekick” Sergeant Horace Edwin Cooke cleared about 100 tons of bombs and shells from about 40 Japanese bunkers (previously sealed with bulldozers) on the island of Betio.

Sergeant Horace (Joe) Edwin Cooke of Hampshire (Photo supplied by his nephew Neil Kilmartin)

On Penang island, they excavated and removed bombs and mines from tunnels and covered trenches at nine major sites.

They entered the tunnels - which were in danger of collapse - and removed 60kg of Japanese bombs. In Betio they excavated and cleared 40 bunkers. Their actions earned them both the George Medal – reputedly Henry refused the George Cross, as this was only given to officers – and the assignment was considered one of the most harrowing and daring since the end of the Second World War.

The London Gazette wrote in January 1967 that 'their drive and complete disregard for personal safety were the two factors which led to the completion of these two difficult tasks in the short time available’ and that they displayed ‘the highest standard of courage and skill'.

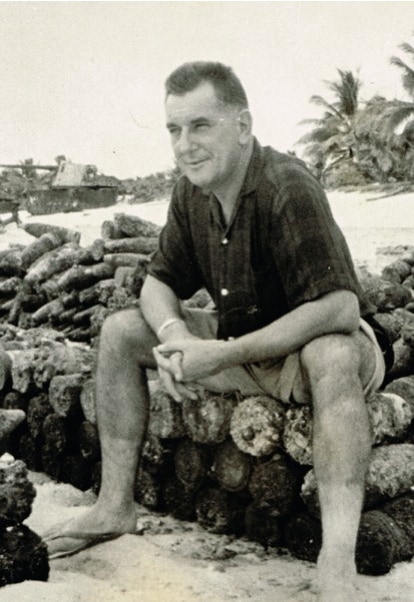

Major Qualtrough sitting on a pile of shells in Betio

Henry Qualtrough retired from the army following his return to Britain in 1966, and having divorced, he moved to the island and, in 1975, married Anne. He became Clerk of Works to Castletown Commissioners and the unofficial bomb disposal unit, dealing with relics of the war by exploding them on the beach.

A keen sportsman, he continued to play rugby and moved to refereeing (after breaking his neck in Malaya). He was an accomplished sketcher, pianist and singer and also was handy with sailing boats. Heather remembered going on one fishing trip in Castletown Bay 'in very heavy weather. On our return, his father having been observing, through binoculars, his grandchildren perilously close to disaster, gave Henry a large piece of his mind! We seemed to not be surprised by what others may have thought of as perilous adventures'.

He enjoyed a pint - particularly at The Sidings or Glue Pot pubs in Castletown - where he would sometimes pass around a glass to raise money for charity.

His friend Dursley Stott said: 'He was a man’s man - he was gruff at times, he had a heart of gold. It is a privilege to have known him.'

The nose-fuze would not budge. The American 600-pounder unearthed on a building site in Kowloon in October 1959 would not yield even to the practised pianist's dexterity of Bomb Squad No 1's commander, 36-year-old Major Henry Qualtrough. The nose of the bomb, one of thousands dropped in 1944 and 1945 in the Allied drive to reconquer territories taken by Japan, had been badly distorted on impact.

Qualtrough, a father of three young children, the youngest not yet two, who were for once in his Army career billeted close by, just across the straits in Hong Kong, had to get this bomb away from the teeming town, now full of refugees from Communist China and the Korean War. The good-looking, broad-shouldered, dark-haired, hazel-eyed Royal Engineer with the fine bass singing voice had already lived a charmed life. He had been one of only two men to survive from a unit of 40 sent to clear the Normandy beaches of mines on D-Day, his 20th birthday.

Was his time up now, married 11 years and two months? It might have been some fleeting instinct from the smuggling heyday of his native Isle of Man that came to his rescue. Some ancestral gene from his old and distinguished Manx boat-building family sprang into action. He called on the help of his team of British and Chinese sappers, and had the huge bomb loaded on to a truck, to take it with as much stealth as he could muster at the wheel of the rough vehicle, get it on to a landing craft, and personally guide the dodgy cargo as far from risk of human reckoning as he dared. He dumped it in deep water and returned, alive. For his gallantry he was made MBE and later awarded the George Medal.

Qualtrough's task was to clear Hong Kong harbour, and Kowloon produced two more especially difficult UXBs, in January and March 1960, one from another construction site, and one sucked out of the sand by a dredger. Neither fitted the descriptions in the American manuals, one having unexpected Chinese markings, and he had to deal, using remote means, with a chemical-delay fuze he found in a tail.

His next challenge was one of the most hair-raising assignments since the Second World War, clearing the notorious Japanese bomb- and sea-mine dumps disfiguring the beautiful landscape of Penang island, "Pearl of the Orient", once part of the British Straits Settlements, then included in newly independent Malaysia, where British military assistance was retained.

Qualtrough and his trusty sergeant Horace Cooke worked around the lily pond in the botanic gardens, and on the fortified hill of Bukit Maung, as well as on at least seven other sites. They disregarded the dangers of unstable picrate crystals from decaying bomb fillings, and very poisonous copper azide from corroding detonators, to reconnoitre covered Japanese trenches and tunnels, many in a state of collapse. They entered one tunnel that had partly fallen in, with the likelihood of more roof falls, and from it removed 60 kilograms of rusty Japanese bombs. They retrieved samples for analysis from every site they explored.

Later on Betio Island, Kiribati, in the mid-Pacific Ocean, then the British crown colony of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands, where American Marines had lost thousands to secure a vital airstrip in November 1943 at the Battle of Tarawa, in which all but 17 of the 4,500 Japanese defenders died, Qualtrough and Cooke excavated and cleared about 40 Japanese bunkers that had been sealed but still posed danger to the large local population. They used detectors to clear the whole island, including a coral causeway, turning up about 100 tons of severely decayed American and Japanese bombs, any of which could have blown them both to pieces.

The two lengthy citations note how in Kowloon "by his confident handling of each incident and his gallant disregard for his own safety," Qualtrough "gave immense encouragement to the less experienced British and Chinese members of the squad" and that at all times on Penang and Kiribati he and Cooke "displayed the highest standard of courage and skill."

Back home, killing time in Horsham, Sussex, Qualtrough found that the prospect of rising higher in the Army away from practical work held no attraction for him. The call of his Manx homeland proved irresistible, and he retired from the Army and returned to Castletown.

There, he married again in 1974, becoming a devoted stepfather to two small children, whom he brought up. He worked as an engineer and building inspector for the Castletown Commissioners, the town's council, and was himself elected on to it. A sector marshal for the TT races, he also prepared courses and helped with organisation for the Southern 100 motorcycle club.

He had a reputation for being outspoken, and in old age became a familiar sight chancing his life to cross Castletown Square, a flag fluttering on the blue mobility scooter his wife had given him when he reluctantly had to stop driving cars, with his Dalmatian dog, Domino, bringing up the rear.

Henry Qualtrough was nephew to Sir Joseph Davidson Qualtrough, speaker of the Manx House of Keys from 1937 to 1960. He attended King William's College, Castletown, where he was head of Hunt house, and Queen's University Belfast, but in 1942 joined the Army in the ranks without taking a degree.

He once considered becoming a doctor, and the thousands of lives he saved by defusing bombs may owe their luck to his having found that he was, at 5ft nine and a half inches, half an inch too short to join his first choice, the Guards.

Henry Percival Qualtrough, bomb disposal officer: born Castletown, Isle of Man 6 June 1924; MBE 1960; George Medal 1967; married 1948 Elizabeth Mary Audrey Peacock (marriage dissolved, died 1993; one son, two daughters), 1974 Anne Cringle (one stepson, one stepdaughter); died Castletown 8 March 2012.

© 2021 by Malcolm Qualtrough, Elizabeth Feisst and the late John Karran Qualtrough.

Hosted by Ask Web Design, Isle of Man.

© Copyright by Malcolm Qualtrough, Elizabeth Feisst and the late John Karran Qualtrough.